Photo by Finnbogi Petursson

Photo by Finnbogi Petursson

There are certain sounds that can’t be born in the confines of a studio or created after countless hours spent fiddling with expensive synthesizers. The meditative drone of a rainforest can’t be replicated by a Juno, and a drum machine will never echo the repetitive, crashing pulse of a waterfall. Field recording, the act of capturing often unexplored terrain with a microphone and a pair of headphones, is one way to archive these sounds.

The early work of pioneers such as Hugh Tracey built the blueprint for field recording, and established its importance as both a form of conservation and musical discovery. It wasn’t without controversy—his recordings were collected long before ethical practices in field recording were widely adopted. Tracey’s 35,000+ strong archive, sourced from across the African continent, remain the largest archive of African music in existence. Recorded over 50 years ago, these sounds live on in new forms today, remixed by the likes of Nabihah Iqbal (formerly Throwing Shade), Auntie Flo, and The Busy Twist on Beating Heart’s South Africa compilation.

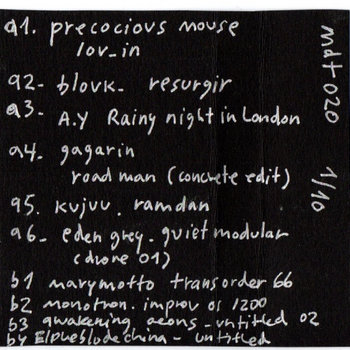

Vinyl

But formerly disconnected lands are now an Airbnb booking away, and recording equipment that was once prohibitively expensive now comes standard in most smart phones. The sonic landscapes of Earth have now been opened to wider ears. The natural ambience of Japanese daily life is explored to mesmerizing effect on wa-on’s Tokyo Yoga Sleep Meditation 001 : Planetary Music. On Kreatur, Berlin’s Soundwalk Collective transform recordings exhumed from former Stasi prisons into rhythmic, brooding compositions. While a dripping of a tap, the hum of a darkened city, or the trickle of a stream can inspire, some artists journey farther than most in their search for the sounds of life.

“Sound is vibration, and because everything on Earth—and elsewhere—is vibrating, it’s possible for it to be considered as a subject for listening and investigation,” says the sound artist Lawrence English. For English, all sound sources offer opportunities for experimentation, and the back catalog of his Room40 imprint showcases many of these investigations. The influence of Turkish architecture on Japanese artist Chihei Hatakeyama turns up in Mirage, while on Qoosui, Haco uses contact microphones to track the electromagnetic waves that emanate from mobile phones and wireless routers, crafting them into glistening, sci-fi soundscapes.

“The world of sound is a complex, chaotic, and ever-evolving zone of engagement,” English says. “You never can really know what is going to reveal itself. Often, there are moments that are so far away from what you might have expected that you’re tempted to stop recording. But later, when you revisit these events, they are totally captivating. They may not be what you went out to discover, but they are equally—or in some cases, more—invigorating than what you could imagine.”

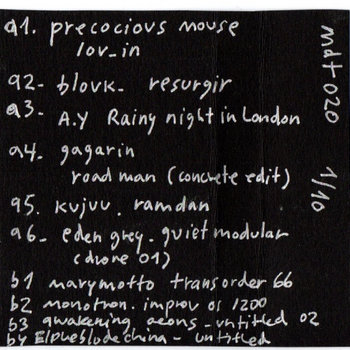

For Alejandra Perez Nunez, known as Elpueblodechina, it’s not just the sounds in these faraway places that compel her to travel, it’s the struggle it takes to reach them. On “Untitled (Field Recording Under Water in Antartica),” taken from Musica Dispersa’s Electrodynamics Compilation, Nunez set her sights on the South Pole. In 2009, Nunez was accepted by the Chilean Navy to travel with them to the South Pole, and after two days aboard one of their vessels, she spent another two days recording the cacophony of melody that exists beneath the ice.

Cassette

“I’m trying to break into places that are not normally allowed to women and artists,” says Nunez over a grainy Skype connection from her home in Chile. It’s a hacking of landscapes, “a critique of this fixed idea that places like Antarctica are unreachable to ‘normal’ people,” as Nunez describes it.

“I had to bend some rules to get there,” Nunez admits. “But our culture is very influenced by the ideas of ‘can’t.’ The idea that we don’t have access to nature and the continent of Antarctica repeats this. We’re told, ‘It’s too far, it’s too unreachable.’ But in fact, why is it not possible? My work questions this ‘impossibility.’”

Using an underwater mic called a hydrophone, Nunez captured a richly textured sonic collage that blips and echoes and turns the ocean into an otherworldly, almost dystopian environment. “You think that it’s an empty desert there, but it’s full, and I wanted to capture what was not visible. I didn’t want to portray Antarctica as this sublime, white continent. I wanted to find the dark side of it. What I found was this richness of life underwater. Through field recording, you become aware of these things that usually, you wouldn’t think of.”

“Sound is like an immaterial material,” says Touch artist Jana Winderen. “It’s all around us. It’s very physical, and I always wanted to go out there and find it. I never wanted to sit inside a studio and regurgitate the same sounds. I want to find little insects eating a leaf and ask, ‘What does that sound like?’”

That ethos has taken Winderen to some of the planet’s farthest edges. She’s recorded the melting of glaciers on Norway’s West Coast, been drenched by gargantuan waves in Japan, investigated the impact of oil drilling near the isolated Norwegian island of Svalbard, and as heard on 2016’s The Wanderer, uncovered the microscopic sound of Earth’s DNA, the plankton.

“Ice is not just ice,” she says. “I’ve been down 90 meters underneath a glacier with my longest microphone cables, and when you do that you can really start to listen to the ice and discover those differences.”

“Field recording” can be a malleable term. A collection of voice notes can be considered your own personal archive, your Instagram an ever-evolving document of your life’s events. Some have the power to transport you to a world that only exists within the vacant space between your headphones. Others, however, simply do not.

“Personally, I’ve sat through many unaffecting recordings, and have been glad when they were over,” says English. “At its best, field recording offers us a privileged position to experience the world through another’s senses.”

For some, the act of unearthing sounds that exist beyond our human abilities is an art form in itself, something that drives the work of Simon Whetham. For his 2018 sound installation Geothermal Activity, Whetham collected infrasonic frequencies—low-frequency sound below the human audibility frequency of 20 Hz—from the area surrounding Iceland’s Grindavík power station to force lava rocks to vibrate and dance, creating their own form of sound.

“I like to use low frequencies for the physical action they can create, moving objects or causing them to vibrate so that what you hear is not the sound itself, but an effect of the energy created by it,” says Whetham. “I try to change sounds, or hear them differently while recording. Using contact microphones and hydrophones, putting small microphones inside objects or actually destroying mics by drowning or burning them.”

On the track “Is the Water Supposed to Be This Blue?”, Whetham turned the vibrations of the German Alps into a nearly 23-minute blissfully-droning sound piece. “Open and Closed Circles” merges field recordings taken from 10 locations over a three-year period, from the Chilean city of Valparaíso and Wongol village in South Korea, to Japan’s Mount Tsukuba and the Icelandic village of Garður. While Whetham’s sound sources are found in largely unknown places, he finds equal inspiration in the everyday.

“When I first began field recording, I wanted to go to these exotic, remote locations and record sounds that no one else could hear, like a sound hunter on safari,” Whetham explains. “But as I became more interested in the act of recording, and the possibilities of recording sounds in different ways, I’ve come to realize that there are sounds around us that can be wonderful and exotic in their own way.”

“The reason why I’m attracted by specific locations is mostly down to a great question: ‘What can I hear there, and what can I learn from that place through its sounds?’” says Yannick Dauby, a French sound artist living in Taiwan. Dauby has spent over a decade recording Taiwan’s 33 different species of frog, often taking him to the farthest reaches of this idyllic, yet demanding, mountainous island. Some of these recordings come together on 蛙蛙哇! Songs of the Frogs of Taiwan Vol.1, where the natural ebb and flow of the Taiwanese forest merges with the sometimes unrecognizable gargles of frogs to create a rarely heard form of ambience.

“When I am listening to a recording, there is a double effect—the aesthetic pleasure of the sound and the sense of the place,” says Dauby, whose field recording-based sound projects he describes as a form of “acoustemology,” a sonic way of knowing and being in the world. “I usually spend most of my recording session exploring the location, recording specific animal sounds, or a detail of human activity. It requires a process of listening to the place, and field recording is a process of description, it helps me concentrating the experience of the place, sharpening and memorizing it.”

While Dauby crafts his work from the hidden beauties of his now home country, drøn have long looked beyond planet Earth to soundtrack our existence on it. The trio behind drøn—Christoph Abert, Frederik Dahlke, and Ingo Zobel—share an obsession with ‘80s sci-fi movies, Amiga-era video game scores, and the experimental soundscapes that used to turn up on early Warp Records releases. They fuse field recordings with synthesized sound to make music that pays homage to the stars.

“We tweak our field recordings so that they sound more electronic while making the synths we use sound more natural,” says Dahlke.

“These two elements traverse the musical order defined by grid or scale, creating something that sounds natural but also electronic and artificial without getting too abstract,” says Abert.

These fascinations came together on HD188753, drøn’s self-proclaimed “trip into outer space” that scores existence on a star system 149 lightyears away. “The combination of natural and synthetic sound generates an interesting contrast and a special feeling for us,” says Zobel. Field recordings taken from their own “deep space probe”—a handheld DAT recorder which Zobel used to record the sounds of his daily routine—were interlaced with the electronic blips, bubbles, and sine waves conjured up within their synthesizer-filled studio.

“Our fascination with space has been with us from very early on, and space inspires many positive thoughts for us,” adds Abert, on how their cosmic music making process comes to life. “Space is a good environment for us to nourish ideas about what life in another environment can be like, and field recording is a great resource for that exploration.”